The story of the Taiwanese F-CK-1 fighter

I found this article online, and decided it was interesting enough to translate it just for the enjoyment of it. Even if you’re not particularly interested in military affairs, this should be a fascinating story involving politics and business. It is written with the average layperson in mind, so some terminology is simplified.

Foreword:

Judging from discussions on internet forums, it appears that most Taiwanese don’t think much of their military and its weaponry. Regardless of your thoughts on the matter, it’s safe to say that the fascinating case of the Taiwanese F-CK-1 (otherwise known as the Indigenous Defense Fighter – IDF), the effort and results, though ultimately overshadowed by the purchase of the F-16, were still impressive nonetheless. I’m sure that if you take the time to complete this article, you’ll have a new perspective and appreciation for the IDF, as well as the complexities behind large international arms procurement.

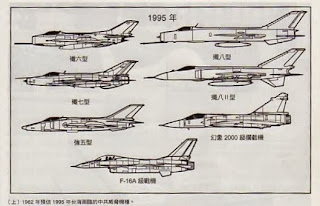

Those familiar with the Taiwanese Air Force (Republic of China Air Force – ROCAF) know that the Dassault Mirage 2000 (France), Lockheed/General Dynamics F-16A/B Blk 20 (U.S.) , and AIDC F-CK-1 IDF (Taiwan) are the Three Musketeers of Taiwan’s air defense. But few know that the IDF, earliest of the three to enter service, was initially intended to counter the Mirage 2000C and F-16A/B. (not the current F-16 Blk 20 version, or the Mirage 2000-5.EI/DI that Taiwan currently operates) In the image above, you can see a chart (dated 1982) listing projections for enemy aircraft from the Chinese Air Force (PLAAF), in 1995. Besides the existing PLAAF fighters, the Mirage 2000 and F-16A are also on the list.

It’s a long story, but it all comes back to Taiwan’s precarious position towards the later years of President Chiang Ching-kuo’s rule. Taiwan’s larger allies had broken off relations, and the Cold War was by no means settled yet. In order to contain the Soviets, America had decided to pursue some form of alliance with China, cooperating on various fronts, with the Europeans following suit. At the time, the U.S. had considered selling the F-16A to China as a means to counter the Soviet Union, while offering to upgrade the navigational systems of the J-8. France, never one to pass up an arms sale, pushed hard for a sale of the Mirage 2000, still in the early stages of development. Taiwan found itself suddenly abandoned, forced to find a way to survive on its own. Upon seeing that it’s desired F-16A might be an impossibility, and the ideal F-20 Tigershark project (intended to replace the F-5) cancelled, Chiang decided to develop the next generation of fighter – the IDF.

Of course, developing a fighter takes more than deep pockets and lots of cash. Few countries have the ability to design and produce fighter jets, and most ultimately end up relying on American assistance. Luckily, the U.S. was already engaged in many weaponry projects (as always), which is a process in which several arms manufacturers produce prototypes based on given specifications, to be selected by the Department of Defense for further development or production. For example, the F-22 is a result of the competition between the YF-22 and YF-23, and the Lockheed Martin F-35 was the winner of a fierce competition against Boeing. This process is what keeps the American military with top-of-the-line equipment, but that isn’t to say that the losing bidder’s product is bad per se, just that there is a limited amount of funding and money to go around.

As such, losing bidders try to recoup their losses by looking for other buyers. The most well-known case is probably the loser of the U.S. Air Force’s Lightweight Fighter (LWF) program, which eventually ended with the selection of the F-16. The runner-up McDonnell Douglas YF-17 underwent a complete overhaul, and the U.S. Navy chose an aircraft based on its design principles, a project that became the now famous and successful F/A-18. But in some cases, no American buyers are to be found, and defense corporations thus turn to overseas markets.

Following strong lobbying by American defense corporations, Congress agreed to a limited technology transfer to help Taiwan to develop the IDF. Many systems from unsuccessful American development competitions ended up on the IDF. The Tien-Chien II (Sky Sword) missile system is essentially an improved version of the runner-up in the AMRAAM competition. The IDF’s radar, weapons system, and ECM all have the marks of American manufacturers. Although losing bids, it was still impressive technology and clearly superior to that of other countries. This “second-life” helped these corporations stay in business, given exorbitant R&D costs, and helped to avoid an imbalance in the military situation across the Taiwan strait. The earlier version of the IDF was put under many restrictions, notably limited engine thrust, keeping the aircraft incapable of disrupting military balance. Designed as an adversary to the Mirage 2000 and F-16A, the IDF was specified as a small and maneuverable defense fighter, with an absolute advantage over fighters coming from long distances.

But the best laid plans of mice and men go awry. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 was rapid, and the need for China to counterbalance the Soviets disappeared. The American strategic situation in the Pacific changed, anticipating correctly that China would attempt to fill the vacuum of power left by the Soviet collapse. As such, a triangular defense composed of Taiwan, Japan, and Korea to contain the Chinese became the new plan. The Americans gave Taiwan arms purchases the green light, and sold not only the F-16A, but other less sensitive weapons as well. France read the tea leaves and followed quickly, selling the Mirage 2000 to Taiwan. Like a long deprived child in a candy shop, Taiwan promptly went on a huge shopping spree. Because of its strong economic development in the 80s, it was blessed with cash to spend, and bought numerous armaments from the largest manufacturers for about ten years. It was as if, after a brush with poverty, Taiwan feared that this would be a once in a lifetime chance. A combination of severe aging in the F-104 interceptor fleet combined with strong French marketing resulted in Taiwan purchasing 960 MICA air-to-air missiles along with the Mirage 2000, advanced for their time. The unfortunate IDF found itself without its hypothetical adversaries, utterly defeated in the arms market. The ROCAF reduced its original order of 250 jets to 130, disappointing not only the IDF development team (Aerospace Industrial Development Corporation – AIDC), but also the American defense corporations operating behind the scenes. From then on, the IDF only sparred with the Mirage and F-16 in training exercises, but under the table, the family conflict continued. Under the banner of national security, the IDF team continued searching for a way back into relevance.

Photo: The only part of the original F-16A/B design remaining in the Taiwanese F-16A/B Blk 20 is the tail.

After Bush senior announced the sale of F-16s to Taiwan, the IDF team, unwilling to admit defeat so easily, began their counterattack. The production numbers directly influenced the livelihoods of thousands, and it was worth fighting for, if not in the skies. After the first American-Taiwanese fighter procurement meeting, AIDC was quite optimistic, because the Americans intended to sell Taiwan the Block 15 version of the F-16 – the last update of the A/B version - and the team correctly pointed out that the IDF was noticeably superior to the Block 15. Of course, Lockheed knew who was working in tandem with AIDC, and that the 15 was indeed inferior to the IDF. Bush senior needed the deal to go through, as the order of 150 F-16s would provide jobs for quite a few Americans, securing him many much-needed votes - but who knew what would happen once a new administration took power? If Taiwan was unsatisfied with the Block 15, the sale was by no means guaranteed. Following the end of the Cold War, Congress was cutting military spending, and Lockheed needed this order badly. As such, it decided to offer the improved F-16A/B MLU (Mid Life Upgrade) that had also been sold to the Netherlands.

AIDC’s first counterattack had been blocked, but up against the F-16MLU, there was still an argument for the IDF, as the Taiwanese noted that this version was designed for fighting on the European continent, and was unsuitable for Taiwan’s tropical climate. They also criticized the MLU as an aircraft without combat experience, or even a prototype – as such, Taiwan would only be serving as a testbed, operating unproved equipment. While releasing such statements through military magazines and the media, the team quickly began work on improving the ground strike capabilities of the IDF, which had already entered service. The key that pleased the ROCAF in particular was the IDF’s ability to use all models of Taiwan’s remaining AGM-65 Maverick air-to-ground missiles. The F-104 and F-5E were due for retirement, and the first full IDF wing was a relief and blessing to the Air Force. Notably, it had all weather combat capability – one demonstration featured an IDF popping out from a valley in the dark, destroying a tank with a Maverick, impressing the Air Force brass. Of course, this type of stunt was a plan to defeat the MLU, which was still awaiting a prototype. And the plan worked – the ROCAF began to reconsider. Upon hearing this news, Lockheed knew that the IDF team was still in action, and something drastic needed to be done.

The most advanced version of the F-16 at the time was the F-16C/D Block 50/52, which Taiwan hadn’t even dreamed of asking for. In an effort to secure the order, Lockheed leadership decided on a tactic that would convince the Taiwanese generals. Essentially, it was “new wine in old bottles”, using the F-16A/B packaging to hold true C/D aircraft, satisfying the Taiwanese and keeping Chinese complaints to a minimum. The ROCAF was overjoyed at this offer – the F-16 had been long awaited, and getting something with the capabilities of the C/D version was something hard to turn down. Its anti-ground capabilities would be downgraded, and Taiwan would indeed be playing the guinea pig, but considering what the ROCAF was getting, and the fact that attacking China was never in the plans, defense needs were not particularly ambitious. As long as you could secure the skies, no soldiers would be landing on Taiwanese coastlines anytime soon.

And so, the IDF suffered another crushing defeat, with Lockheed (General Dynamics, at the time) taking the first round cleanly. Ironically, because the Chinese didn’t complain as much as expected, and the plan to put new wine in old bottles was more trouble than it was worth, the end result was simply to lock down active radar homing (ARH) missile capability, restrict ground attack options, and place F-16A/B tails on C/D models. Lockheed finished by creating the new Block 20 designation, but it was basically “new bottle and new wine with an old label.” Some critics complained that the Taiwanese were ripped off, as the Air Force paid above market price for the A/B. Obviously, the ROCAF wasn’t planning on admitting anytime soon that these aircraft were not, in fact, A/B

And so the F-16A Blk 20 and the Mirage 2000 began to join Taiwanese fighter squadrons. The first few years of integration went relatively smoothly, despite all the fighting under the table. The fake A/Bs with actual C/D capability lived up to the reputation, and the F-16s became the stars of the fleet. The IDF team and its American backers were very displeased with what they saw as dirty and unfair tactics of Lockheed – under what logic should the IDF shoulder various restrictions, while Lockheed was pulling underhanded tricks like switching labels? The complaints got to the point where the Americans had had enough, agreeing to remove the radar and thrust restrictions on the IDF, which explains why later versions of the aircraft enjoyed a nearly 1:1 thrust to weight ratio, giving it a huge boost in capability. In the five to six years after losing the first round to Lockheed, the defense corporations supporting the IDF team hadn’t remained idle – they understood that the F-16 had a weak point to take advantage of – the U.S. refused to allow anti-ground and anti-sea capabilities, particularly the latter. If Taiwanese F-16 Block 20s had anti-shipping ability, it would utterly disrupt military balance in the strait. The team accordingly began showing deep interest in the indigenous Hsiung-Feng II anti-ship missiles. If the IDF were able to utilize this weaponry, it would be an absolute game changer.

The plan to equip the IDF with Hsiung-Feng II anti-ship missiles caused a stir after the news was intentionally leaked to the media. This was shortly after the 1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis, and the Taiwanese military knew that one of its weaknesses was inability to retaliate against Chinese targets, and was planning accordingly. The air-launched version of the HF-IIE air-to-ground missile was the key to this plan - although it was still in the planning stages, the idea was that if the IDF were able to wield the HF-II, it would also be able to use the HF-IIE, designed for use against land-based targets, no longer restricted to dropping few iron bombs, or conducting Close Air Support. Air-launched anti-ground missiles enjoy not only a mobility advantage – mounted on aircraft and launched at high speed and altitude, effective range is far beyond that of land-based systems. Besides the distance provided by the fuel within the missile itself, you add the aircraft’s effective combat radius (with drop tanks included) to that, with altitude extending distance further. If using the center of the Taiwan strait as a calculation point, the northernmost city in range is Shanghai, and the southernmost range includes nuclear power plants.

Insiders could tell immediately that AIDC planned to further develop anti-ground attack ability into retaliatory strike capability, creating new value for the IDF in the Air Force. Of course, the Americans understood this, and expressed their opposition. But there are different types of disagreement – “opposed to Taiwan developing anti-ground capability”, and “opposed to Taiwan developing its own anti-ground capability – if you’re going to do it, at least do it with our products.” And so when the U.S. determined that the HF-II anti-ship technology for the IDF was mature – but before mass production and deployment began – the Americans announced availability of AGM-84G Harpoon Anti-Ship missiles for the F-16A/B Blk 20. Interestingly, Taiwan already was in possession of the ship-based version of the Harpoon – the RAM-84 Sea Harpoon, something that was “loaned” together with its Knox-class frigates. As such, there wasn’t much attention paid to this at the time, and the Chinese didn’t particularly protest. But strategically speaking, ship-launched and air-launched Harpoons were an entirely different game altogether. The American decision dealt a blow to the IDF team’s plan A, but they believed that there was no possibility for the sale of anti-ground missiles in the future (theoretically, striking ships could be categorized as defensive usage, but ability to strike ground targets opens up offensive capability), so if the IDF were able to deploy the HF-IIE, it would become Taiwan’s premier counter-strike platform, using a combination of weapons that the U.S. was unwilling to sell, securing its position as one of the big three.

Alas, plans never survive first contact with the opponent. With a large change in the international situation, the plan slowly evaporated. The U.S. had come to the realization that rather than using the unpopular method of restricting sales, it was better to sell as much as it could at once. This made money, and even a country as rich as Japan found it difficult to develop indigenous weaponry – the ridiculously overpriced Mitsubishi F-2 was the perfect example - much less third-rate powers. Plus, America was beginning to view Chinas a serious potential adversary, slowly changing their strategic emphasis to the West Pacific. In addition to making money by actively arming the first line of defense in its allies, it would reduce the burden on the U.S. military, already taxed by its engagement in Iraq and other regions. So long as things didn’t get out of hand, its Pacific allies could take care of most issues by themselves – it was a win/win situation. Most importantly, the U.S. was already transitioning to the next generation of fighters like the F-22 and F-35. Though current American inventory was still considered top of the line to other countries, there was no longer a need to protect it judiciously. Selling these weapons would not pose a threat to American forces, and if there was a way to get pass them off while there was still interest, it was a good business deal. Under the circumstances, any country with enough liquid cash or resources and a need for defense became goose for the slaughter.

These were the circumstances – the Americans holding a fire sale on military inventory – that Taiwan conducted its first change in government, determined to develop the ability to “fight beyond its borders”. The goals of both sides matched perfectly. As the IDF team was working closely with the American tech teams to develop an upgrade in ground strike software, the U.S. used a window of opportunity in which supply and parts for the Block 20 were accompanied by the export version of the LANTIRN system. The original LANTIRN was comprised of two pods - the AN/AAQ-14 for targeting, and the AN/AAQ-13 for navigation, exclusively used by the U.S. armed forces. (the downgraded export versions were designated as the AN/AAQ-19 Sharpshooter and AN/AAQ-20 Pathfinder, respectively) On first glance, these were simply two small pods carried aboard the aircraft – but in truth, they significantly increased the F-16’s combat effectiveness, allowing them to fly at low altitudes, at night and all weather, attacking ground targets with a variety of precision-guided weapons. Technically speaking, American F-16C/Ds and Taiwanese F-16A/B Clock 20s were the same, in that they didn’t have terrain masking flight and strike ability installed – it was all possible due to external LANTIRN pods. When the U.S. first sold the F-16s to Taiwan, the pods were not included, leaving the Block 20s without precise ground strike ability, essentially capable only of tossing unguided iron bombs – hence initial reports claiming that Taiwanese F-16s were only capable of air combat. But upon acquiring the export version of the LANTIRN, Taiwan’s Block 20s enjoyed close to full ground strike ability. The IDF was already able to deploy the AGM-65 Maverick, and so to counter, this batch of LANTIRNs was accompanied by the newest infra-red homing AGM-65G2 variant, giving the Block 20s the ability to strike targets at night with pinpoint accuracy. In contrast to the earlier version of the Maverick, which required television guidance and could only be used in the daytime with good visibility, this variant was a significant upgrade over the types employed by Taiwanese aircraft.

Taiwan acquired the export version of the pods, without automatic terrain-following flight ability, or the ability for command headquarters to automatically designate targets for its Maverick missiles. The Americans never sold the full version of the LANTIRN pods to its allies, fearing that if the tech fell into enemy hands, it would be impossible to defend against low-flying attack aircraft. But considering that most of Taiwan’s metropolitan targets in China were along the coastline or next to large rivers, there were plenty of terrain features for fighters to follow at night, even without automatic terrain-following ability. And so, for the first time in 50 years, Taiwan had the ability to strike vital ports and cities on the east coast of China. Taking the war to the enemy’s borders was no longer just a slogan.

Of course, the F-16 receiving such anti-ground capability was a nightmare for the IDF team. The original strike and anti-ship upgrades no longer interested the Air Force, and upon seeing the nighttime strike results of Block 20s, the ROCAF was looking forward to receiving the next batch to fully equip other F-16 squadrons. Now, F-16s deployed from Hualien Airbase on the east coast of Taiwan could fire Harpoon missiles, effectively shutting down enemy ships coming from the northern or eastern Pacific, providing an obstacle for many of China’s ships in the northern fleet. The last thing that put the nail in the coffin for the IDF’s attempt to win favor in the Air Force was the sale of the Raytheon AN/ALQ-184 Electronic Countermeasure (ECM) pod, and the AIM-120C AMRAAM.

The AN/ALQ-184 ECM pod was top-of-the-line American equipment, and only used on fighters based in American territory – Taiwan was the first export case. In contrast to the previous generation; the Westinghouse AN/ALQ-119 and Northrop-Grumman AN/ALQ-131, the AN/ALQ-184 possessed stronger scanning and counter-jamming ability, all automatically without requiring pilot input. It would filter out threats to the aircraft, actively jamming them with narrow waves. Besides confusing enemy illuminating radar, it also disrupted the seekers of air-to-air missiles and SAMs. This made it exceedingly difficult for the enemy to lock on to aircraft, or track targets after missile launch. It wouldn’t be a stretch to describe it as the ultimate electronic defensive countermeasure for U.S. aircraft. Taiwan of course didn’t dare to hope for this piece of equipment, but it noted with surprise that China did not protest strongly against Taiwan’s acquisition of export LANTIRNs. Upon further analysis, it was believed that protests were generally with an eye to the political level, not military or strategic.

Selling Taiwan new aircraft or ships clearly expressed American support, but the effect of selling truly game-breaking equipment like targeting pods wasn’t immediately obvious to the untrained eye. When purchased together with replacement parts, most ignorant Taiwanese reporters figured there wasn’t a need to report about it. And so Taiwan began to lobby the Americans for advanced electronic equipment, hoping to acquire an “invisible” advantage.

After over ten years of arms purchases, Taiwan was finally getting the hang of things. At military conferences and negotiations, Taiwan argued that this ECM pod was the textbook definition of defensive weapon, and should not be subject to American restrictions. In addition, China hadn’t protested, and the sale of the pod made its way into Taiwan alongside parts for fighters and missiles. The initial purchase was for a small number, but with the addition of the second order, Taiwan received 128 pods in total, enough for the 140 F-16s.

The AN/ALQ-184 completely defeated the IDF upgrade program. Besides its advanced jamming ability, it more importantly came with the support of the American electronic spy network. Everyone knows that the U.S. has bases all over the world, and tirelessly catalogues the electronic signatures of enemy electronic weaponry, with combat experience in the Persian Gulf War and various military exercises against Russian-made weaponry. The AN/ALQ-184 had information regarding the electronic parameters of Russian-built radars, beam length, and capabilities - all part of software upgrades, allowing it to effectively jam enemy systems. The biggest difference between physical weaponry and “soft” weaponry is that soft weaponry is constantly updated with new information and databases, giving operating air forces a decisive advantage.

Air-based Harpoons, AN/AAQ-20 navigation pod, AN/ALQ-184 jamming pod –three items purchased at different times, with different effect – combined, they were a deadly combination for use by the ROCAF. Imagine F-16A/B Block 20s launched from airfields on the eastern coast, emerging from caves tucked in well-hardened mountain hangars in the dark, equipped with AN/AAQ-20 navigation pods, skimming over the Pacific at super-low altitude, heading north to hunt Chinese ships steaming south to support an amphibious invasion. While in flight, they activate their AN/ALQ-184 jamming pods to disrupt the targeting systems on the Chinese vessels, and with each Block 20 carrying two Harpoons, 4 aircraft to a flight, two waves would comprise of 16 Harpoons launched from multiple directions. Aircraft equipped with advanced ECM pods have always been a threat to ships, especially long range Harpoon missiles with a high hit percentage. In fact, it’s quite possible that opposing ships might not even detect the threat from Block 20s when the missiles are already on the way, and if the Taiwanese Air Force were to lose control of the skies in a war, it would still have the option of chipping away at enemy ships to weaken landing forces.

Compared to the F-16 Block 20 deploying air-launched AGM-84 Harpoons, AN/AAQ-20 navigation pods, and AN/ALQ-184 jamming pods, the IDF was undeniably inferior as a sea denial platform. The only remaining weapon system capable of upstaging the F-16 was the Tien Chien-2 (Sky Sword) midrange air-to-air missile. The American technological support for the TC-2 came from the losing bid of the AMRAAM project, as Motorola-Raytheon turned to Taiwan, bringing its project back to life with the TC-2. At the time, the United States had not yet approved sales of the AIM-120 series for use on Taiwan’s F-16s, thus leaving only the IDF and Mirage 2000-5 with the ability to deploy active radar homing (ARH) missiles, equipped with the TC-2 and Mica, respectively. The Mirage specialized in high speed high altitude intercepts, and medium to low altitudes were handled by the F-16 and IDF. Because the Block 20 only had Semi-Active Radar Homing (SARH) Sparrow missiles, this meant that the IDF was the only aircraft capable of firing ARH missiles at medium engagement altitudes.

The biggest difference between ARH and SARH missiles is the method of guidance. In short, ARH missiles have their own seeker, while SARH missiles rely upon continuous guidance and radar illumination from the launch aircraft until impact, leaving it vulnerable to attack. With fire and forget ability, ARH missiles allow pilots to immediately engage their next target, or conduct evasive maneuvers as needed after firing. As such, medium range ARH missiles are standard weaponry on next generation aircraft. The Russian version of the AMRAAM is known as the R-77 (NATO code AA-12) – early variants of the Su-27SK imported by China did not possess radars capable of utilizing the R-77, and as such the missile was not purchased, and that became the excuse used by the Americans to deny Taiwan AIM-120s.

But in truth, what made the AIM-120 the premier air-to-air weapon in U.S. inventory wasn’t just the missile’s own capabilities, but its datalink with early warning aircraft. Taiwan had just received the E-2 Airborne Warning and Control System (AWAC) aircraft at the time, and lacking a database to link to, the AIM-120 would be unable to be used for full effect. Under the circumstances, the TC-2 was an important bargaining chip in the hands of AIDC, justifying its existence. The Mica was more maneuverable and its design excelled in dogfighting, with high angle pursuit capabilities comparable to close range heat-seeking missiles, but it suffered from limited range. The IDF team saw the American refusal to sell the AIM-120 as the ideal opportunity, and pushed the Motorola-Raytheon to conduct improvements on the TC-2. The goal was to give it a longer range than the Mica, focusing on mid to low level threats. The American defense contractors planned on using payment from upgrading the TC-2 to keep the supply and development chain active, and if deployment and storage was possible in on a humid tropical island, it would prove the TC-2 well-suited for use in naval environments. With this technology and experience, Motorola-Raytheon would be well placed for American missile competitions in the future. Using the same missiles as the Air Force didn’t exactly please the U.S. Navy, which hoped to develop its own medium range ARH missile.

With Motorola-Raytheon’s ambition and AIDC funding, the TC-2 upgrade project developed quickly, hoping to at least reach the capabilities of the AIM-120B. Due to the lack of AIM-120s for the F-16 Block 20s to use, the teams worked to incorporate the TC-2 into the F-16’s arsenal. If this plan was carried out successfully, it would prove the TC-2 as a valid option for all countries that also operated the F-16, but were denied the AIM-120. Motorola-Raytheon even used various diplomatic channels to contact several East Asian countries hoping to convince them to put off purchases of the AIM-120, awaiting the new “Naval combat AMRAAM”. It also sought out those still working on the F-5E/F in Taiwan, proposing the Tiger 2000 – an upgrade of the F-5A/B/E/F fighters, providing them with basic versions of the TC-2, giving these old fighters the ability to launch ARH missiles as well, something that would be attractive to poorer countries still operating the F-5 as the backbone of their Air Forces. But exposure makes targets, and Motorola-Raytheon’s plans displeased the AIM-120 contractors greatly, particularly its attempts to take over the export market. Besides lobbying the American government for sales of the AIM-120 to Taiwan, there “conveniently” appeared reports indicating that Motorola-Raytheon illegally sold sensitive advanced seeker technology to Taiwan, which cut off seeker sales for the TC-2 upgrade project temporarily, delaying assembly.

After acquiring the first and second batch of Su-27SKs, China began demanding the R-77 from Russia, to counter the ROCAF’s MICA and TC-2. Besides negotiation production of Su-27s (Chinese-produced version known as the J-11) by Shenyang Aircraft, China also wanted the more advanced SU-30MKK, giving the Russians little reason to deny the R-77 to China. It was understood that China receiving the R-77 was an inevitability, and the Taiwanese Air Force indicated to the Americans that if the U.S. still refused to sell the AIM-120 to Taiwan, then at the very least it needed to allow the TC-2 to equip the F-16. In a sense, the Americans were forced to pick from one of two plans. The U.S. had not made a decision at that point, and the team behind the TC-2 made a convincing argument for it as an alternative to the AIM-120. The IDF team even claimed that the improved TC-2 had capabilities rivaling that of the AIM-120C, and even if Taiwan was allowed to purchase the AIM-120, it would only end up acquiring older A or B variants. As the U.S. military itself was still awaiting shipment of AIM-120Cs, there was no conceivable way for Taiwan to acquire them earlier, as demand exceeded supply. If AIM-120Cs were actually ordered, they would be out of stock and unavailable in a crisis at any rate. Adding to this was more information indicating that the Chinese import of Su-30MKKs and R-77s was ahead of schedule, pushing the ROCAF leadership into an uncomfortable position.

Within every crisis lies opportunity. The focus of Taiwan’s defense acquisitions had turned from “hard” weaponry to “soft” electronics, and the ROCAF planned to establish a wartime database that could be utilized in tandem with the American and Japanese LINK-16 datalink. The key to the first wave was Air Force AWAC early warning aircraft, F-16 squadrons, land-based radar, and asset control systems. The Air Force originally intended to incorporate the Mirage 2000 into the plan, but faced strong French opposition, as integration meant giving American technicians access to core systems of the Mirage, something that the French Dassault company was unwilling to do. With the French refusing to cooperate, the IDF stepped up as a back-up, and found itself added to the plan. Under the circumstances, this was the perfect chance – with the Taiwanese denied the AIM-120, there was no option for the government but to fund the TC-2 upgrade, giving it datalink abilities. This was crucial because the later versions of the AIM-120 were increasingly deadly due primarily to its datalink guidance. The AIM-120’s newest guidance method was composed of a three part “pre-firing guidance, datalink guidance, active-radar homing” process. Most introductory material leaves it at that, but close observation reveals American ambition, because when F-22s are deployed with AIM-120D/C7/C5s, opposing pilots are knocked out of the sky before they realize what happened.

“Pre-firing guidance, Datalink Guidance, Active-Radar Homing” meant that after being fired from an aircraft, the missile would not turn on its own seeker, and would rely upon location, speed, and height data from the launch aircraft to calculate a preset intercept point. Of course, the target might have changed its course during this time, which is where the datalink steps in. Once the firing aircraft detects that the target has changed its speed, height, or heading, it will send updated information to the missile already in flight, creating a new intercept point, allowing the missile to continue tracking without turning on its own radar - the missile turns on its internal radar only after reaching ideal tracking distance. Advanced targets may detect the threat at 10 miles out, giving perhaps 8 to 9 seconds of reaction time. Older targets may have less than 3 seconds between a threat warning from their Radar Warning Receiver and impact.

It’s difficult enough already to face a missile that flies at Mach 4, makes constant adjustments, and doesn’t turn on its active radar seeker until the last moment. Later AIM-120 series developed a datalink with long range early warning aircraft, making the threat even more effective. The powerful tracking capability of AWAC aircraft (E-2T, in Taiwan’s case) dwarfs that of fighters, and friendly aircraft can be directed to fire against targets locked on by AWACs before the targets even know it’s there. Fighters directed by AWACs don’t even need to turn on their radar – they just need to follow directions, flying to designated locations and firing off their missiles, since the E-2’s mission control computers use the datalink to send firing information to fighters to guide their missiles. Once the missile is launched, the E-2 takes over, continuously updating the missile with the latest target information, allowing the launch fighter to proceed to its next target. The superior tracking range of the E-2 allows it to essentially hit enemy aircraft before they can close to weapon range, before it can even be “seen” by targeted fighters or bombers. The F-22 is a textbook example – once in full service, the stealth fighter will be directed in place by AWACs, fire a missile, and relocate immediately. Targets are shot down before they even realize they are being tracked.

After the F-16 and IDF were upgraded with Link-16 capabilities, AIDC and TC-2 development team decided it was time to advocate Link-16 for the TC-2 as well, paving the way for deployment on F-16s. This would mean a significant batch of TC-2s needed to fully equip Taiwan’s F-16 squadrons – but it was precisely the preparation of this electronic database for linked combat that convinced the AIM-120 manufacturers to begin lobbying strongly for export to Taiwan. If all preparations were in place but the TC-2 taking advantage of Link-16, this system could be used in all countries operating the F-16, dealing a big blow to AIM-120 exports. At this point, two things happened - intelligence received news indicating China would be receiving the R-77 within the next two years, and the Americans approved the sale of two new E-2T AWAC aircraft, changing the situation completely.

News of China receiving the R-77 worried Taiwan greatly. Besides requesting the AIM-120 from the U.S. once more, Taiwan also simultaneously ramped up the TC-2 upgrade project, needing a backup plan to avoid any military imbalance if a purchase proved impossible. There were several problems with AIM-120 production at the time – while the U.S. hoped to sell the AIM-120 in order to stall development of the TC-2, there simply wasn’t available inventory available for the ROCAF. The newest C version had just entered service, and production was already saturated just fulfilling huge orders from the American military. Even if the government agreed to a sale, Taiwan would be forced to either purchase the older A and B models, or wait patiently in line for orders of the C model. But as China was purchasing existing inventory of the R-77 from the Russians, the missiles would be ready to go after contract finalizations and training. Taiwan was in a severe time crunch.

The ROCAF wasn’t overjoyed with its limited AIM-120 choices, particularly since the TC-2 was by now supposedly on par with the AIM-120B. The Americans argued that China had purchased older existing stock of the R-77, with capabilities vastly inferior to the AIM-120B, and since the U.S. military was switching out the A/B for the C, it would be willing to sell this older batch at a discounted price, and with rapid shipment. Price, in particular, was alluring to the Air Force, still needing to equip its F-16 fleet. It was also a politically popular sell to the public, since most people are clueless about the difference between the A, B, and C versions. But there were also dissenting voices within the military, arguing that if only As and Bs were available, giving the TC-2 upgrade project full support was a better idea. From their perspective, Taiwan controlled a very limited airspace, without strategic depth, completely outnumbered by the Chinese. Balance was kept in the strait only through smaller numbers of superior weaponry and training. If Taiwan did not acquire a decisive advantage in air-to-air weaponry, it would lose the military arms race quickly.

This caused Taiwanese leadership to hesitate about purchasing the AIM-120, and lean towards the upgraded TC-2 project. It was at this point that the Air Force decided to make one last probe into purchasing the newest AIM-120C5 series, the only model worth waiting for. If the Americans rejected, then Taiwan would place all its bets on the TC-2. What ultimately caused the U.S. to change its policy may forever be a mystery, but the facts are that the Americans agreed to sell Taiwan 200 of the newest AIM-120C5 missiles, catching many military observers off guard, including the Taiwanese military itself. Perhaps the U.S. was worried that if Taiwan successfully developed its own mid-range missile, America would find itself unable to control the situation in the future, but if it restricted Motorola-Raytheon from assisting Taiwan in development, causing Taiwan to fall behind in air superiority, imbalance in the strait would become an uncomfortable truth. Of course, this is all speculation after the fact. At the time, this sale not only exceeded the expectations of the Taiwanese military, but also caused Hughes (more accurately, Hughes-Raytheon at this point. It’s complicated.) quite a headache figuring out how to get the new AIM-120s to Taiwan.

The threat facing Taiwan was clear. China had purchased older versions of the R-77 with capabilities between the AIM-120A and B, so acquiring inventory was not a problem for them. But the AIM-120C5 production line was filled with American orders, unavailable for Taiwan in the near future. The Taiwanese military would have to explain to the legislature, opposition political parties, and public why it had paid good money in advance for products that couldn’t be delivered for years. It would get particularly ugly in the court of public opinion if China conducted public tests of the R-77. And so the two sides came to an understanding – Taiwan would wait in line for production of new missiles, but the Americans would first provide AIM-120Cs originally slated for use on aircraft stationed in Guam. If hostilities broke out, these missiles could be shipped to Taiwan for use immediately. Publically, this allowed the U.S. to argue that it was holding the AIM-120C5s “to maintain balance in the strait” until China received the R-77. Of course, this was a story full of holes. Raytheon was already deeply behind schedule for AIM-120 production just fulfilling U.S. orders. How in the world was it possible that 200 missiles were available for storage at Guam? At any rate, this is the fiction that allowed Taiwan to eventually receive a batch of AIM-120C5s, and another 200 AIM-120C7s later on.

As to what model the missiles held in storage actually were, nobody knows.

appreciate your precious information about f ck 1 fighter. Is there any additional information about flight characteristics of that aircraft?

ReplyDeleteI found this really interesting, thank you for putting it together and translating it. I was just over in Hualien and saw many jets landing and taking off.

ReplyDelete